By Dr Mark Baynes

Drawing inspiration from current trends in popular music, it is probably fair to say that songwriters, including students at MAINZ, often gravitate towards diatonic-based composition. Who would blame them? Diatonic-based composition is an intuitive solution that allows for a direct path to lyrics and melody, the heart and emotion of any song if you like. Of course, plenty of songs use devices such as modal interchange and secondary dominants to introduce non-diatonic harmonic spice into their music too, but it is often the exception rather than the norm. In the second year of the Bachelor of Musical Arts degree, I teach an advanced composition class, in which we explore alternatives to diatonic composition. We sometimes move completely away from it. This article discusses that method, prescribing a different approach to melodic and harmonic relationships that I hope you enjoy.

DIATONIC

Like many musical terms, the word ‘diatonic’ has its origins in Ancient Greece. The first part of the word ‘dia’ loosely translated means ‘across’ or ‘through’ giving the whole word the meaning of ‘through a key centre’. In the key of C, a diatonic chord progression would consist of chords drawn from C, Dm, Em, F, G, Am, Bdim or Cmaj7, Dm7, Em7, Fmaj7, G7, Am7, and Bm7(b5), and an accompanying melody would likely be based on either C major or C major pentatonic scales.

ALTERNATIVES

To explore alternatives to diatonic harmony, it may be useful to first consider a subdominant, dominant, and tonic premise that underpins functional harmony, defined by the regular use of chords four (or two minor), five, and one. These chords are the ‘strongest’ chords in any given key as their harmonic relationship to the tonic is closest. If you take the key of C major, then the chords in order of harmonic importance and strength are as follows: Dm7 – G7 – Cmaj7.

TABLE 1 – THREE ‘TYPES’ OF CHORDS

Examples of Minor Chords |

Examples of Dominant Chords |

Examples of Major Chords |

| Dm9 | G9 | Cmaj7#11 |

| Dm11 | Bdim7/G | Cmaj9 |

| Dm | G9#11 | C6 |

| Dm7 | G7#5#9 | Cmaj13 |

| Dm7b5 (Fm6) | G13b9 |

CHORD SCALE RELATIONSHIPS

After carefully separating chords into three distinct camps, it is necessary to deduce which notes are best suited for each one of the three types of chords, and in what capacity. A system of identifying a chord/note relationship is necessary to help guide a composer to possibilities depending on colour, emotion, vibe etc.

ROOTS AND FIFTHS/GUIDE TONES /COLOUR TONES/’WRONG NOTES’

The following table can be used as a guide to provide clearer thinking in terms of chord/note relationships, and it breaks down the 12 chromatic tones against each of the three types of chord – minor, dominant, and major.

TABLE 2 – CHORD/NOTE RELATIONSHIPS – MINOR CHORDS

| C minor | Degree | Roots & Fifths | Guide Tones | Colour Tones | ‘Wrong’ |

| Db | b9 | √ | |||

| D | 9 | √ | |||

| Eb | b3 | √ | |||

| E | 3 | √ | |||

| F | 4(11) | √ | |||

| F# | #11 | √ | |||

| G | 5 | √ | |||

| Ab | b13 | √ | |||

| A | 6 | √ | |||

| Bb | b7 | √ | |||

| B | 7 | √ | |||

| C | √ |

TABLE 3 – CHORD/NOTE RELATIONSHIPS – DOMINANT CHORDS

| C7 | Degree | Roots & Fifths | Guide Tones | Colour Tones | ‘Wrong’ |

| Db | b9 | √ | |||

| D | 9 | √ | |||

| D# | #9 | √ | |||

| E | 3 | √ | |||

| F | 4(11) | √ | |||

| F# | #11 | √ | |||

| G | 5 | √ | |||

| Ab | b13 | √ | |||

| A | 6 | √ | |||

| Bb | b7 | √ | |||

| B | 7 | √ | |||

| C | √ |

TABLE 4 – CHORD/NOTE RELATIONSHIPS – MAJOR CHORDS

| C major | Degree | Roots & Fifths | Guide Tones | Colour Tones | ‘Wrong’ |

| Db | b9 | √ | |||

| D | 9 | √ | |||

| D# | #9 | √ | |||

| E | 3 | √ | |||

| F | 4(11) | √ | |||

| F# | #11 | √ | |||

| G | 5 | √ | |||

| Ab | b13 | √ | |||

| A | 6 | √ | |||

| Bb | b7 | √ | |||

| B | 7 | √ | |||

| C | √ |

By breaking down notes into four distinct areas we can view note choices in a sliding scale from safe-dangerous, simple -complex, consonant-dissonant etc. Ultimately, taste and context should be your guide.

For successful application, melodies should probably be built from a combination of coloured notes, guide tones (3rds and 7ths), and roots and fifths, as variety is likely a good thing. In cooking, too much spice may ruin a meal, yet simplicity may render it boring too. If you are looking for a great example of a balanced approach to chord/note relationships in action, then check out Black Hole Sun by Soundgarden. The melody begins with coloured tones, using a major 6th, and a #11 before resolving to 3rds and 5ths at the end of the verse. Please note that ‘wrong’ notes should probably be described as ‘handle with care’ notes, being the most dissonant category, they can be problematic if used without care, but ultimately, they can still be useful. Context is everything.

ONE NOTE EXAMPLE

Another way to look at chord/note relationships perhaps is by exploring the options available of just one note. Below is a non -exhaustive list of harmonic options that support the note F.

TABLE 5 – THE MATRIX OF POSSIBILITIES FOR A SINGLE NOTE (NOT EXHAUSTIVE)

| Note Choice Example | Chord Options | Scale Degree | Root & Fifth | Guide Tone | Coloured Tone |

| F | Fmaj7 | R | √ | ||

| Bbmaj7 | 5 | √ | |||

| Ebm7 | 9 | √ | |||

| Dbmaj7 | 3 | √ | |||

| Cm7 | 11 | √ | |||

| Bm7b5 | b5 | √ | |||

| Dm7 | 3 | √ | |||

| Bbm7 | 5 | √ | |||

| Ab13 | 6 | √ | |||

| G7 | 7 | √ | |||

| Ebmaj7 | 9 | √ | |||

| Gbmaj7 | 7 | √ | |||

| Abmaj7 | 6 | √ | |||

| Bb11 | 5 | √ | |||

| Eb9 | 9 | √ | |||

| B7#11 | #11 | √ | |||

| A7aug | #5 | √ | |||

| Bmaj7 | #11 | √ | |||

| E7b9 | b9 | √ |

As you can see, there are many options available to choose from, and that is just for supporting one note!

RANDOMNESS AS A CREATIVE TOOL

A good way to start extending harmonic options whilst composing is using randomness, which can be a useful tool

in composition to help break yourself out of learnt patterns and clichés. We tend to write the same tunes over and over, tell the same story if you like, and we should seek tools that help us explore the unknown.

SKELETON (MELODIC FRAMEWORK)

In addition to randomness, it is important to build a skeleton melody first. Melodies have identifiable frameworks called a melodic skeleton, outline, or structural melody. This framework carries basic information about the harmonic (and sometimes) rhythmic flow of a melody. In analysis, notes are heard as part of a melodic framework because they have qualities that attract the listener’s attention, impress themselves on the listener’s memory, and thus become important reference notes as the music unfolds in time.

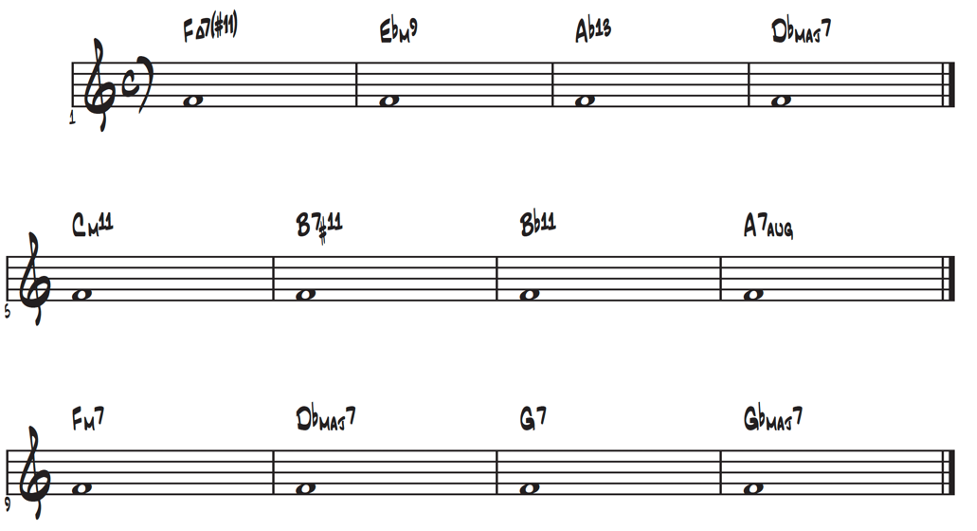

Try experimenting with an economic skeletal melody that, once established, can help guide you towards a fully developed melody. For example, you may choose a single note to create a chord sequence that supports it in different ways. Below (Figure 1 and Figure 2) are examples of a single note melody supported by a random but curated selection of appropriate harmony.

Figure 1 – Examples of a single note melody supported by a random but curated selection of appropriate harmony. You could then develop that single note melody into something more substantial and decorative.

Figure 2 – Single note melody developed

This composer’s toolbox method is of course just another tool to use in a composers toolbox, it is there to help a composer have more options to draw from rather than being an aesthetic imperative. As discussed, composers can fall into the trap (for better or for worse) of writing the same piece of music time and time again, as we are guided by our own musical instincts. At times this can be a good thing as it may provide listeners with assurances of style and genre, however there may be a downside to overly predictable music too. Although this method may be prescriptive in nature, after excusing the pun, it might be, on occasion, just what the doctor ordered.

BIO: Dr Mark Baynes is Programme Leader for the Bachelor of Musical Arts degree at MAINZ, Auckland; A degree program that fosters students’ ability to find their own musical voice, culminating with the creation of a capstone project such as an album, film score or music for game audio. Mark writes regularly for NZ Musician, is a host of the 95bFM Jazz Show, and forms one half of group Goldsmith Baynes, as heard on Waiata Anthems and live at the Aotearoa Music Awards 2021.